FINSCI is a major project into Finnish science capital. At the University of Eastern Finland, a sub-project within FINSCI focuses on primary school children and their parents.

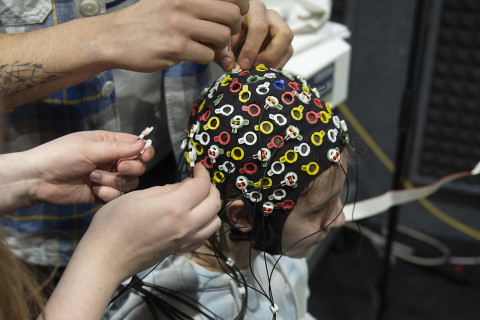

“I don’t feel anything, although my friends said I might feel a pinch,” says Mira Kastinen, a 6th grade pupil as she puts on an EEG cap, which will measure the electrical activity of her brain.

Mira is one of the pupils participating in the Fostering Finnish Science Capital research project, FINSCI, conducted in collaboration between the University of Eastern Finland, the University of Turku and the University of Helsinki. The aim of the extensive project is to investigate and foster Finnish science capital in order to provide everyone with better tools to understand phenomena such as climate change.

The University of Eastern Finland’s sub-project within FINSCI, “Parental Science Capital and Children’s Science Literacy and Learning”, was launched this year and is led by Professor Sari Havu-Nuutinen. According to her, the sub-project focuses especially on investigating and fostering the science capital of children and their parents in the school setting. The research group seeks to explore the conceptions of science and its significance among primary school children’s parents, as well as their support for their children’s science education.

“Mira, on the other hand, got to wear the cap because we wanted to explore what kind of things guide pre-teens’ decision-making. All answers will be processed anonymously, so pupils don’t have to be nervous about how their answers will be assessed.”

Science, beliefs or everyday experience?

The EEG cap cannot read thoughts, despite the sixth graders having their doubts to the contrary. The cap has conducting wires and electrodes that sit on the scalp tightly, thanks to a gel-like substance. A curve then appears on the computer screen, illustrating the pupil’s neurocognitive processes.

“Pupils are presented with statements about various themes, such as climate change, the clothing industry and health. They are given three answers to choose from: one based on science, one based on beliefs and one based on everyday experience and emotions,” Research Assistant Jenni Bäckman explains.

When pupils think about their answers, researchers get neurological data on what is happening in their brain. Pupils are also asked to verbalise their thoughts and to justify their answers.

“The neurological data gets sent to the University of Helsinki for analysis, while we teacher educators here at the University of Eastern Finland will analyse children’s verbal answers,” Havu-Nuutinen says.

Previously, similar research has only been conducted in adults, so this is the first time children's neurocognitive processes are being studied in the context of statements presented to them.

Laboratory technology strengthens research

Mira Kastinen is not anxious about participating in the study or responding to the statements because, according to friends who’ve already participated, the statements are “easy questions of opinion”.

Research assistants Iiris Kangasniemi and Andreas Fischer – who also studies in an international Master’s degree programme –, are helping Mira get prepared for the study. He adjusts the EEG cap for each pupil and reassures those who are nervous about the situation.

“I’m surprised by how well pupils understand English. Most of them also answer my questions very fluently.”

Besides working as a research assistant, Fischer is also writing a Master’s thesis in the FINSCI project.

The instruments used for neurological measurements are part of the logopedics laboratory at the University of Eastern Finland. Havu-Nuutinen is grateful for the opportunity to borrow the modern equipment for research in educational sciences, too.

“The new laboratory has proven invaluable for us in this project. Thanks to having access to the latest technology, we’ve also been able to strengthen our collaboration in research into cognitive neuropsychology,” she says, pleased.

Understanding science and science professions

Another objective of the University of Eastern Finland’s sub-project is to carry out various classroom interventions among 4th grade pupils in order to foster their science capital. The interventions are aimed at examining children’s everyday decision-making and problem-solving processes.

“Pupils of that age are still on a very concrete problem-solving level. Based on classroom discussions with pupils, we are exploring what kind of things or knowledge children rely on as they tackle everyday challenges, such as those related to nutrition and energy,” Havu-Nuutinen says.

Children have also been introduced to scientific instruments and they have, for example, looked at water samples under a microscope. The interventions are of varying lengths, after which children’s science capital can be examined as a whole.

“We are also planning an evidence-based guide for teachers, which will make it easier for teachers to address science capital in the classroom.”

The guide gives examples of how to talk about science on each lesson, for example. Teachers are also encouraged to get familiar with scientific texts with their pupils, and to learn about the people behind them. In other words, to learn about all the work that is being done for science.

Havu-Nuutinen says that the project also has a working life perspective, which is also increasingly emphasised in the curricula.

“We know that young people are less and less interested in STEM subjects, and this is a global problem. The idea is to spark pupils’ interest in science and technology early on, and to help them see the multitude of science professions out there.”

Parents, too, are included in these interventions, and they will be sent a survey on the family’s science capital. Pupils will also get homework in which parents are involved.

The goal is for pupils to be able to make decisions relying on scientific knowledge, and not be fooled by non-scientific nonsense, polarised opinions or manipulation.

Sari Havu-Nuutinen

Professor

Aiming at good media literacy

According to Havu-Nuutinen, the goal of science education is good media literacy, i.e., for children as young as those in primary school to be able to tell true and false apart. Even later on, they'll be able to make their decisions relying on scientific knowledge, and not be fooled by non-scientific nonsense, polarised opinions or manipulation.

“Having shared science capital promotes justice and equality in society. The foundation for this is laid already in school and during studies, but lifelong learning also accumulates science capital in everyone’s own social networks. This is why information obtained from research of this kind is important.”

The FINSCI project is conducted in collaboration between the University of Turku, the University of Helsinki , the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Science Centre Heureka, the Finnish Science Centres ry, and Skope ry. The project is funded by the Strategic Research Council at the Academy of Finland.

https://www.finsci.fi/