Itä-Suomen yliopiston ja Luonnonvarakeskuksen kehittämän suosimulaattorin avulla voidaan laskea, milloin suometsien ojat kannattaa kunnostaa.

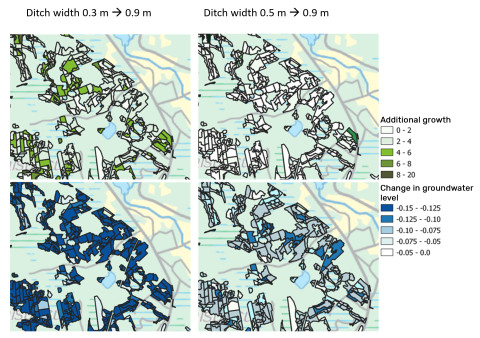

There are nearly five million hectares of drained peatland forests in Finland, amounting to roughly one fourth of the country’s annual stand growth. The Peatland Simulator is a tool that can be used to predict the effects of ditch network maintenance on the growth and yields of peatland forests, as well as on groundwater levels. These effects can be examined in different ditch depths, strip widths, sites and forest stands.

“Out of the different forest management measures, ditch network maintenance causes the most harm to the environment. If we can avoid unprofitable ditch network maintenance, we end up preventing environmental harm and saving money in the process,” Associate Professor Ari Laurén says.

He is the lead developer of the new Peatland Simulator that is already being tested. In the future, the Peatland Simulator will also calculate carbon balance. This makes it possible to examine the effects of ditching and stand growth on greenhouse gas emissions, as well as on dissolved carbon and nutrient loads that end up in water systems.

“We are also running a project where we build a browser interface for the Peatland Simulator. This, too, will be made available to everyone.”

The environmental impact of mistakes can be serious

In Finland, the 1960s was a time of intensive ditching. Their environmental impact began to be understood more broadly in the 1980s, and the Finnish government withdrew its support for new ditches in the 1990s. Discussion around carbon balance and climate change, and the effects of forest drainage on water systems, have put the management of peatland forests under a new kind of microscope.

“Peatlands and peatland forests are delicate ecosystems. Mistakes in their management can have a serious impact on the environment. This is why various simulation systems play a crucial role in the modelling of these impacts. They are also important because the regulatory environment can change even rapidly.”

Indonesia, for example, experienced widespread peatland and forest fires in 2015, leading to rapid introduction of new legislation that prohibits letting the peatland groundwater level to sink below 40 centimetres. Associate Professor Laurén was one of the developers of a model that calculated the ideal places of building blocks in the drainage canals of tropical peatlands.

With the drainage canal system spanning 1,000 kilometres, the number of possible alternatives was infinite, but the amount of money wasn’t.

“This is when mathematical models and optimisation come into play.”

Optimisation is needed to solve different vicious ecological problems.

Ari Laurén

Associate Professor

Optimisation offers tools to solve vicious ecological problems

The Forest Ecosystem Modelling Group at the University of Eastern Finland develops models for the management of forestry-related environmental issues. Currently, for example, the group is testing a distributed nutrient balance model in the catchment basin of Lake Puruvesi in eastern Finland. The model can be used to calculate the effect of spatiotemporal variation in forest harvesting on the nutrient load that ends up in water systems. The nutrient balance model is being developed in collaboration with the Natural Resources Institute Finland.

The researchers are also looking for solutions to optimise plant production in tropical cultivable forests and peatlands, and to reduce greenhouse gases. They are currently developing a Plantation Simulator than can be used to calculate how the use of fertilisers, or other management of the nutrient balance, improves the yields of different forests.

“Optimisation is needed to solve different vicious ecological problems.”

Photo: Ditching of peatlands has changed Finnish water ecosystems.