“Studying old manuscripts is a very slow and laborious process, leading to very little anything published. But if I do my job well, the things I discover can live on for centuries, helping many other researchers and taking the whole field forward.”

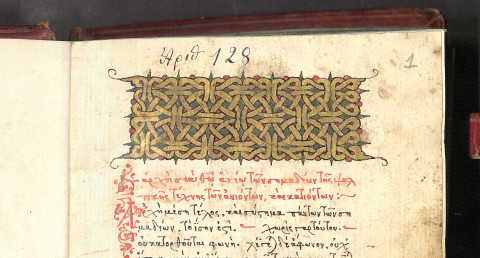

This is how University Lecturer Damaskinos Olkinuora sums up the motivation behind his research. He studies old manuscripts, focusing mainly on Greek-language texts written between the 7th and the 14th century. His research takes place in Greece, mostly in the monasteries of Mount Athos, which harbour the largest collection of Byzantine medieval manuscripts in the world. In his civilian life, he is also a monk in the Monastery of Xenophontos on Mount Athos.

“I do most of my work in my own monastery, but it is easy to go and do research in the other monasteries, too. Monastery librarians are very strict about who can access certain texts, but for a monk, doors open up easily.”

The Monastery of Xenophontos has just completed as massive, EU funded digitisation project, where old manuscripts, ancient correspondence, photographs, icons and pieces of art were archived and digitised.

“This offers researchers an easier access to old materials, since it is now possible to study them also off-site. For instance, women are barred from our monastery, and this is why I find it important to make the materials digitally and equally available to everyone.”

Olkinuora describes his work as basic research that offers tools for other researchers in the field.

“In other words, I do research that opens up new targets of research for other researchers. Eventually, this kind of research also serves as a basis for new learning materials for universities, for example.”

This requires a researcher to be exceptionally well-versed in the field.

“If we think about impact factors, i.e. how significant a scientific publication is, well conducted research into manuscripts can have an impact on the field that will last for centuries. I feel that by studying manuscripts, I can contribute to theological research far more than by publishing individual papers. Yet, this is the kind of research that isn’t really supported by education policy decisions globally,” Olkinuora criticises.

Rewriting history

Food stains, handwritten notes and comments, drops of beeswax from candles. When one holds a book that is a thousand years old, the pages tell a tale of other people who have held the book, too.

“It’s a rewarding feeling. That’s when I concretely feel like I’m a part of history.”

Indeed, manuscripts are used to write history – sometimes even to rewrite it.

“Some years ago, a passage from an old papyrus made the headlines by claiming that it contained a reference to Jesus’s wife. However, a later examination of the passage revealed that the reference wasn’t necessarily to a wife, and the entire papyrus turned out to be a forgery.”

Olkinuora says that manuscript research rarely catches the attention of the media – unless of course there’s breaking news, such as evidence of Jesus having had a wife; something that could rewrite history.

“That happens every now and then, but perhaps not on such a scale. People seem to assume that all historical texts preserved to our time have already been found, studied and published. That’s not true at all, since we keep on finding old theological texts, allowing us to constantly reassess history.”

This reassessment is always based on profound understanding of the field. In addition to one’s own discipline, the area’s history, languages and geography must be understood, too. Putting together pieces of a text is often like putting together a puzzle: some pieces may have been destroyed in a fire or damaged by humidity, or they have been stolen altogether.

“Research never focuses on a single manuscript; instead, the researcher must have at least some sort of understanding of all Byzantine manuscripts in the world. Among other things, one has to know old water stamps and be able to identify the scribe by handwriting. In addition, the manuscript must be correctly dated.”

When manuscript texts are drafted for publication, different versions of the same text are compared in order to find the correct form. At that point, the work is no longer mechanical, and the researcher’s own judgement and expertise will play an important role.

Technology helps

When dealing with manuscripts that are hundreds of years old, they must be handled according to a certain protocol. Hands must be washed before touching them and clothes must be dust-free. No food or drink is allowed in the room where manuscripts are handled, and the air humidity has been optimised to preserve old paper.

“Earlier, researchers used to wear cotton gloves to prevent oil from the skin from damaging the paper. Now, however, we know that this oil can actually preserve the paper, making it less fragile.”

The preference is that manuscripts are no longer separately photographed for each researcher, since flashlight can cause damage. This is why digitisation is the best alternative.

“This offers all researchers digital access to the original texts while at the same time protecting fragile papers.”

Palimpsests are a whole different matter. They are manuscripts from which text has been washed or scraped off, and the material has been reused. Parchments used to be very expensive and, if a text wasn’t considered valuable, it was scraped off and written over.

Indeed, modern technology offers the best aid for studying palimpsests.

“Most of them can only be read under ultraviolet light. Earlier, researchers also used chemicals, but they were too damaging.”

I wouldn’t talk about a calling; the monastery simply felt like I had come home to a place where I belong.

Feeling homesick

Correct interpretation of old manuscripts requires mastery of the Greek language. Besides holding a doctorate in theology, Damaskinos Olkinuora has also completed a Master's degree in Greek language and literature.

“I spend so much time in Greece and with the Greek language that I sometimes feel like my Greek is better than my Finnish.”

He also holds a diploma in Byzantine music, awarded by the State Conservatory of Thessaloniki.

“A long time ago, I was on student exchange in Greece and a part of me never left. Back then, I had the chance to visit the monastery that is now my home, and I got a strong feeling of wanting to stay there.”

“I wouldn’t talk about a calling; it simply felt like I had come home to a place where I belong.”

Olkinuora’s life is now divided between two places: he has one home on Mount Athos and the other in Finland where he spends time both in his childhood home in Janakkala, and on the Joensuu Campus of the University of Eastern Finland.

“Monks have always worked in theological faculties. I feel that my work as a university lecturer supports my monkhood. It feels quite natural.”

Life in the monastery follows a strict schedule. Depending on the time of the year, monks will start their day between midnight and three in the morning.

“Night is the best time for prayer. We spend our days working, such as attending to the garden, painting icons and cleaning. My days are mostly spent doing research. In the evening, we get together for a service.”

Being a monk means absolute obedience to the abbot of the monastery.

“Even when I’m in Finland, I want to follow the monastery’s schedule. Otherwise life outside the monastery is quite different, as I’m responsible for everything.”

Life in Finland doesn’t seem impossible, though.

“However, I’m always feeling homesick and missing my monastery.”